Imakay Research Hub

Artigo

EU-Mercosur: the trade agreement after the Brazilian elections

18/11/2022

Bruno Santos Fonseca, PhD researcher at Portuguese Institute of International Relations (IPRI-NOVA)

The political agreement reached on June 28, 2019, between the European Union and the Mercosur member states (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) has defined the future of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement that has been in the pipeline for more than two decades and could reach more than €40 billion in imports and exports. However, a series of economic and political obstacles in the countries of both blocs, as well as the estrangement between the EU and the Brazilian government in recent years, have left the ratification of the agreement pending.

A protracted trade agreement

The Common Market of the South, commonly known as Mercosur, has Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay as founding states and signatories of the Treaty of Asuncion, and its fundamental purpose is to create trade and investment opportunities through the competitiveness of each country’s economies with the international market. Besides the founding states, Venezuela, also a member, is suspended; and Bolivia is in the process of joining.

The interest in a rapprochement between Mercosur and the EU emerged shortly after the beginning of the 1990s, but it was not until 1995 that the blocs signed the Mercosur-EU Interregional Cooperation Agreement, allowing them to reaffirm their desire to give way to negotiations for a future free trade agreement. The basis and action points in the agreement are intended to combat the difficulties inherent in competition and trade barriers between the two blocks – high import duties, complex procedures, technical regulations and standards that differ internationally – by presenting countermeasures to remove these limitations and preserving fair conditions between them.

For the Mercosur bloc, the main purpose of the trade agreement is to unblock about 92% of the bloc’s total imports from the European Union and, in contrast, to unblock 91% of European imports from the Mercosur states – estimates indicate that the South American bloc will have free trade agreements and actions that will make up about 23.5% of the region’s global GDP. In this way, key areas and sectors of Mercosur will make room for the demand and development of real economic opportunities: access of agricultural products to the European market and sharing of services and knowledge, allowing for an increase in the economic competitiveness of the bloc.

For the European Union, the agreement will allow the elimination of excessive tariffs, enabling European companies to export – cars, machinery, technological equipment, food products, etc. – for Mercosur countries; trade promotion, following different moulds from those practised in international trade; rejection of protectionism by two of the world’s largest economies, through the implementation of fair rules and high standards; and development of policies that protect workers and the environment (combating deforestation and climate change), with increased social responsibility – points present in the agreement and defended by the European Union, as well as by Mercosur on similar issues.

However, with the achievement of a political understanding in 2019 by both parties, many criticisms have arisen in order to undermine and stall its conclusion, especially for the environment and sustainability discussion, which, for the European Union, is formulated as a primary element. According to Frederik Stender, an economist at the German Institute for Development and Sustainability (IDOS), in an article published on the London School of Economics (LSD) blog, “the agreement has been criticized for neglecting poor environmental standards and the failure to protect indigenous peoples in Brazil,” revealing the issues that have led to the stumbling block within the European Union.

In addition, on numerous occasions, the political and economic conjuncture in Mercosur countries has led to stagnation of negotiations, not only because of Argentine protectionism, but also because of the paradigm shift experienced in Brazil in 2018 with the election of Jair Bolsonaro – all these dimensions have nurtured constant impasses caused by issues that are structuring for the European Union, such as human rights, the environment, and the agricultural sector.

The importance of the environmental agenda

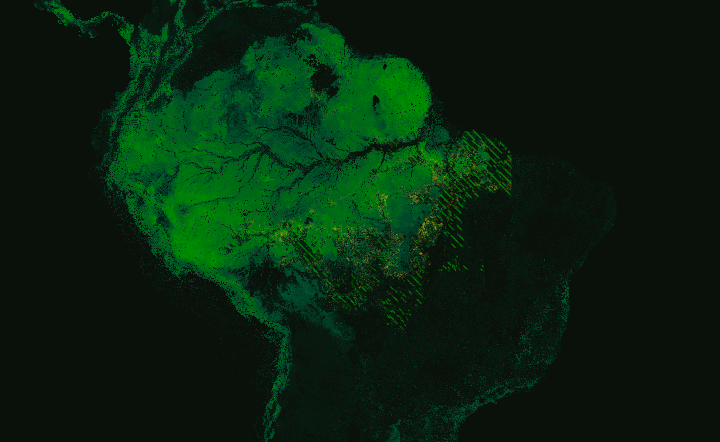

Over the past few years, following the broader agreement in principle decided in 2019, much criticism has come from various spheres of government and individuals in both regions. On the one hand, in the European sphere, leaders of individual member states and ambassadors, through MEPs and members of the European institutions (e.g. Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevicius), have addressed in unison environmental concerns and the need to come up with concrete measures to combat deforestation of the Amazon rainforest; on the other hand, several members of the Brazilian federal government (Bolsonaro’s mandate) have accused the European counterparts of using the environmental issue as an unfounded argument, just to defend an agenda of trade protectionism.

Environmental protection issues are one of the preconditions for the European institutions, especially the European Parliament so that the obstacles caused by the “low credibility” political action of Bolsonaro’s government can be addressed and thus the free trade agreement achieves success.

In addition to this criticism in the political sphere, civil society and many organizations have also replicated the discomfort with some points and problems arising from the trade agreement, such as Client Earth, Veblen Institute and La Fondation Nicolas Hulot pour la Nature et l’Homme, among others, denouncing that there were structural flaws in the negotiations. For Client Earth, the European Commission “did not adequately consider the potential impact of the agreement on issues such as deforestation of the Amazon forest and the use of dangerous pesticides in agriculture,” as well as the consequences that the lack of a strategic impact assessment would have on the defense of indigenous communities in the forest region. This action demonstrated the necessary transparency and assessment of the impact on biodiversity and sustainability, not only on the part of the European Union but in equal sum on the part of all the Mercosur states, with the greatest impact on Brazil, which has the largest area of the Amazon.

The environmental issue will be the necessary change so that the agreement can advance in all its dimensions, political, social and commercial. There has been a change in positions, especially since the results of the second round of the Brazilian elections, held on October 30, which declared the victory of candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. As an example, during the government of the current Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, Norway suspended the transfer of funds to combat deforestation and, after the confirmation of Lula’s victory, the Norwegian government announced that it will resume these funds, predicting that the environmental issue will no longer be a topic of disagreement between Mercosur and the European Union.

What to expect after the Brazilian presidential elections

The aftermath of the Brazilian election results revealed a change in the political paradigm and, likewise, the notorious polarization that will accompany the policy action of the now-elected Lula da Silva’s government. This change that threatens on the horizon will bring many difficulties in the removal and surgical “cutting” of policies and measures that led to the removal and interregnum in the advancement of the EU-Mercosur agreement.

With the victory of Lula, with 50.9% of the votes against 49.1% for Jair Bolsonaro, the European Union sees another opportunity to unlock the ratification of the agreement, due to the environmental consignments presented by the newly elected president. Still, there are some caveats: parts of the agreement may be renegotiated to protect the Brazilian industry, which may confirm another delay in the conclusion of an agreement that has been decades in negotiation. According to Reuters, during the election period, then-candidate Lula da Silva mentioned that he wanted an agreement in “six months”, showing interest in concluding the free trade agreement quickly.

Josep Borrell, high representative of European Diplomacy, mentioned within the scope of his participation in a meeting of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), in Buenos Aires (Argentina), that the EU-Mercosur agreement “is much more than a trade agreement: in the current geopolitical context, it is a way of revealing our willingness to act together on the world stage,” adding that the fight against climate change, deforestation and the protection of biodiversity will be included in an additional protocol to the EU-Mercosur trade agreement – signs that negotiations and determinations are beginning to unlock, especially given the current Brazilian political horizon.

Despite the caveats, the new perspective with regard to negotiations between the European Union and Mercosur seems promising, not only because of the current manifest reality of Brazil, a country of obvious relevance in the bloc, but also because of the European Commission’s desire to split the trade agreement in order to accelerate the entire ratification process by developing and adopting concrete and conclusive measures – according to sources linked to the agreement negotiations (commercial, political and cooperation).

In short, not only will the European Union’s action be arduous: Brazil and the other founding members of Mercosur will also face obstacles to reaching an understanding among themselves and of society’s own demanding action. In this sense, the goal will be to make the trade agreement a stronger link between the European Union and Mercosur, since there are opportunities to foster and bring closer a market of about 780 million consumers, creating geostrategic, economic and development sharing benefits – with the ratification of the agreement, it could have an impact on Brazil’s admission process to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) since the EU-Mercosur approximation would benefit such process.