Imakay Research Hub

Artigo

How foreign policy issues were addressed by candidates for the presidency of Brazil in 2022

28/10/2022

Stephanie Braun Clemente, PhD candidate in International Relations (UERJ)

It is intriguing to know what presidential candidates are announcing on foreign policy issues, an essential public policy for all states. As has been increasingly highlighted by global events, no country acts alone in the international arena. On the contrary, it is imperative to cultivate good relations and establish connections with regional and extra-regional partners to pursue national interests.

Therefore, it is essential to understand how the candidates intend to direct Brazil’s foreign policy. Although this is not the central focus and hardly appears in the campaigns in question, the proposals and interpretations put forward by the candidates should be analyzed to evaluate what the next government intends to do.

Traditionally, these external agendas were relegated to a position of little prominence in the country’s electoral disputes, since it was believed that “foreign policy does not bring votes”. However, over the last three decades, this scenario changed, and presidential candidates started to address these issues more often. However, a new change can be highlighted in the current elections, since, due to a series of domestic political problems, international agendas have been dealt with marginally in the campaigns.

For this analysis, we investigated the government programs of 3 of the 11 registered candidates. We consider that the presidential aspirants who have prominence in such contests are those with at least 5% of voting intentions. According to Datafolha, those who meet this requirement are Lula da Silva (PT) – at 50% -, Jair Bolsonaro (PL) – at 35% – and Ciro Gomes (PDT) – at 6% -.

The government plans of these contenders were investigated more specifically. Before examining the details at a general level, it is possible to perceive a dispute between the presidential candidates over narratives about Brazil’s current position in the international system, which reflects how each of them intends to act in the foreign arena.

Following Lula’s government plan, Brazil is still lagging behind and isolated internationally and must return to an “active and proud” foreign policy; for Bolsonaro, the country already “occupies a position of great importance in the international community”, which demonstrates the intention to maintain foreign conduct in the same terms as it is today; finally, Ciro’s plan emphasizes the need for the country to improve its international position in the development ranking.

Leading the polls: Lula da Silva

Besides rescuing the golden times of the so-called “active and proud” foreign policy, which positively marked the candidate’s former administrations, other relevant points are also mentioned in Lula´s current project. However, it should be noted that foreign policy topics appear less frequently than expected: out of 21 pages, only about 1 of them is dedicated to foreign affairs.

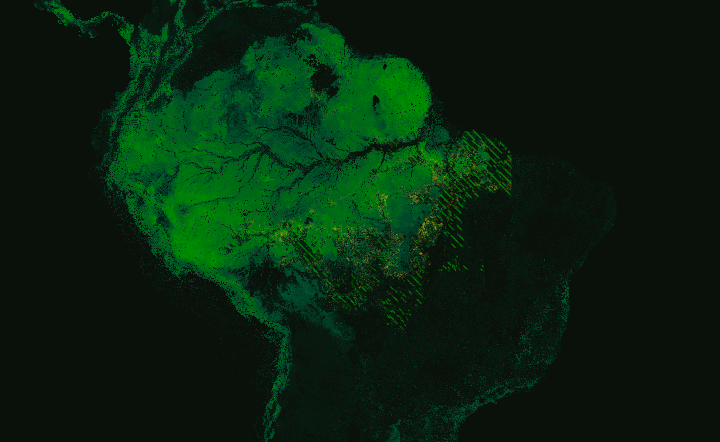

Despite the little emphasis placed on foreign policy compared to domestic policy, what is said is important for outlining what this administration intends to pursue. They emphasize the importance of Brazil seeking to regain international respect by strengthening its sovereignty and regaining its global role. They state, optimistically, that despite what has been put into practice in terms of environmental and foreign policies by the current government, the recovery of prestigious international credentials would not be difficult.

It is stressed that South-South cooperation with Latin America and Africa will be rebuilt; development aid to poor countries will be resumed, through instruments of “cooperation, investment, and technology transfer”; the expansion of Brazil’s role in multilateral organizations will be defended; and regional and extra-regional mechanisms will be strengthened, such as Mercosur, Unasur, Celac, and Brics.

They emphasize that the country will defend its sovereignty by “freely establishing the partnerships that are best for the country, without submission to anyone,” which means a more pragmatic foreign policy will be adopted. In addition, they state that “defending our sovereignty is defending the integration of South America, Latin America, and the Caribbean,” seeking security and promoting development regionally.

From these points it is possible to understand that the current plan is based on what was done in the past, supported by the belief to replicate it with a new government in charge. However, we cannot affirm that such an attempt would be successful since domestic and international contexts are quite different today from those of the early 2000s.

The current president: Jair Bolsonaro

Bolsonaro’s government plan is different from what we saw in the 2018 elections. It adopts a less ideologized tone and uses more complete analyses of international issues. Moreover, in comparison with the plans of the other candidates analyzed here, it is the one that devotes more space to foreign policy.

As a way to distance himself from his former government’s plan, there is a marked inflexion in the tone of criticism that was previously uttered against the liberal international order. There is no mention of “globalism” and there is an attempt to reaffirm the values of Brazilian diplomacy. The document seeks, at least rhetorically, to defend democracy, sovereignty, and the universalistic concept of foreign policy. It emphasizes the search for attracting investment and cutting-edge technology, the imperative of reducing external dependence, and the diversification of economic relations.

It states that “a Government Plan must generate certainties” and that in this sense, in the event of re-election, the government would continue in the implementation of “structural changes and reforms”, which would not have been more comprehensive between 2019 and 2022 at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic and the occurrence of the war between Russia and Ukraine.

Unlike the plan above, Bolsonaro does not present any particular proposal or mention of Latin America, South America, or the Caribbean. The Americas region is restricted merely in terms of constituting sources of investment, markets, and cooperation partnerships: “with countries around the world; and with our geographic surroundings in the Americas and the South Atlantic”.

Other instances end up taking the stage for the candidate, such as the OECD, the IMF, the UN, the WTO, the UN Security Council, as well as the G-20 and BRICS. Furthermore, the importance of achieving bilateral and multilateral agreements is stressed, with explicit mention of The European Free Trade Area (EFTA).

As far as this government project is concerned, it should be noted that what was put into practice in terms of the country’s foreign policy during the years this administration was in power, diverges from what is being planned for possible reelection. Thus, it is abstruse to believe in such promises and even more complicated to glimpse paths of prestige for Brazil in the international system in a future reelection.

A third option: Ciro Gomes

Ciro’s government project disclosed on the TRE website says little about the country’s international relations and does not bring proposals of what it intends to achieve regarding foreign policy. However, the candidate himself disclosed that it is possible to deepen his government project through his book published in 2020, entitled “Projeto Nacional: O dever da esperança”. It was through this book that the information below was collected.

Chapter III, “the new geopolitical context”, contains analyses, and general and generic proposals of the PDT candidate for Brazil’s foreign policy. One of the ideas defended is that the country should seek to prevent other powers from sabotaging its development and maintain the secular traditions of our foreign policy – peaceful resolution of disputes, self-determination of peoples, respect for the sovereignty of all countries, and an international order based on law and not on violence. Following his approach, countries should be guided by trade preferences to overcome “our technological backwardness in sensitive sectors”.

Moreover, a point that draws attention is the affirmation that Brazilian diplomacy cannot allow itself to be led by ideological fanaticism and that we need a “rebel” financing mechanism that points us in a different direction from the “failed prescription” given by the United States. This does not mean that we should antagonize hegemonic powers, but rather that we should (re)build a relationship based more on pragmatic lines.

Furthermore, the book addresses the country’s position in a globalization scenario and focuses on Brazil’s relationship with Latin America and the BRICS countries, “the best opportunities for strategic partnerships for the country”. It is emphasized that Latin American integration is “an economic and strategic imperative provided for in the Constitution” and that initiatives to promote improvements in regional infrastructures, such as the Bioceanic Corridor, the Pacific Highway, and the South American Energy Ring, should be supported. About the Brics, Ciro argues that “a government legitimately committed to the national interest” should use these initiatives as a way of state development.